‘I’m The Face, baby, is that clear’

This is the opening line from ‘I’m The Face, flip side to ‘Zoot Suit’, The Who’s first ever single.

The record celebrates ‘Ivy league jackets’ and ‘side vents five inches long’ – helping create the idea that a ‘Face’ was a tastemaker, someone to copy and look up to.

Song titles deliver real clues as whether this is the right soundtrack for whatever identity listeners fancy trying on in that moment.

But magazine titles can do more. They might explain frequency and a point of view, but as a constant outward-facing presence, they can create aspirations and a sense of self that’s as valuable as the content itself.

The New Yorker, The Lawyer, and if you like, The Lady, are definitive articles, fine examples of allowing an audience to reflect a brand’s identity as part of their own. The NME’s value is surely as much to with its Enemy of The State alter-ego as any number of gig reviews.

On a smaller scale, Mark Perry’s punk fanzine Sniffin’ Glue, and Fraser Allen’s Scottish football magazine Fitba only lasted a few issues, but the intense identity associations of their titles has done much to ensure their immortality.

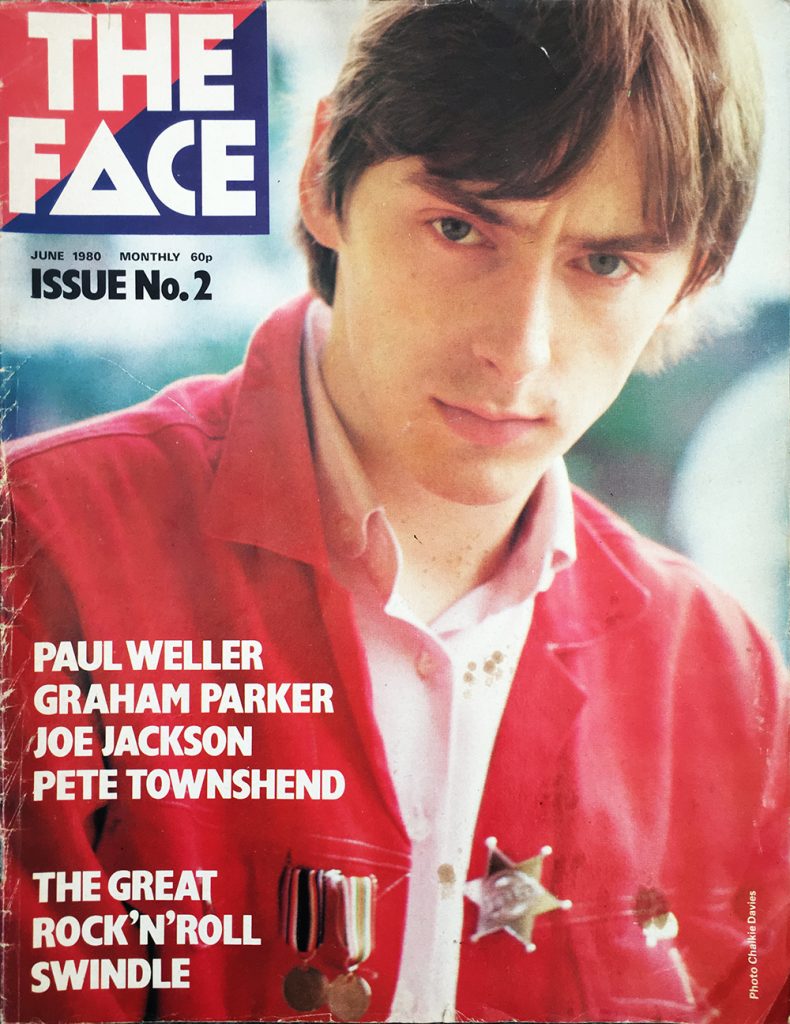

Which brings us to The Face, now relaunched after an absence of 15 years.

This news produced an outpouring of overheated media coverage, suggesting it was some kind of sacred chalice, changing lives and making stars of all who touched its hallowed pages.

And to be fair, for a while it really was a joyous moment of being with one’s tribe – living as an insider, part of something special.

But how will it fare this time around, given the existence of that thing called The Internet?

Paul Gorman’s book The Story of The Face has plenty of details about its rise and fall, culminating with Bauer closing the title in 2004 and selling the rights to Wasted Talent in 2017.

At this stage it had no income and no audience, but it still had real value.

Why, even now, do I have a big stash of Face magazines on my shelves? I throw magazines away all the time, so why could I not let these go?

Somehow, I knew it was important.

Paul Smith thinks so too, as wandering about his high-end shirt shops you now encounter piles of vintage Face magazines, delivering some kind of mystical cachet to his brand.

This value goes way beyond content. It’s not about what’s on the pages, it’s about the values behind them. In particular, it’s about what sort of person the reader feels like when they’re engaged with these ideas.

Today, the six most valuable social media companies are those that are closest to your face, or failing that, contain an awful lot of other peoples’ faces.

Facebook is number one, obviously. Second placed You Tube is face heavy and has ‘You’ in the title. Third, fourth and fifth are messaging apps, which are as close to your face as a mobile device will permit. Number six is Instagram, built almost entirely on selfies. By contrast, down at number 12, Twitter is named after the delivery method, not the user’s identity.

The genius of The Face may well start with the intimacy of its name. The title identifies the cover subject as an influencer, but the name also reflects that status back on the reader – it elevates both.

The new magazine is not expected until September, but the website and social channels are already launched, carrying a fairly conventional mix of fashion, politics and pop culture.

This is where shit gets real. Like a band reforming after a 15-year absence, we now have new material to compare against the greatest hits.

And the news is good. The site has plenty of smart stories – Tristan Cross’s piece on the future of social media a particularly good example. Meanwhile, the Instagram skilfully posts old and new – as illustrated by their brilliant David Lachapelle shoot with Tupac Shakur on the anniversary of his death

The challenge is how to differentiate the brand to those who know nothing of its history. The Face used to have the waterfront to themselves, but from Vice through to GQ Portugal and dozens of other well-regarded brands, the fact that Face editors have deemed a story worthy of inclusion will no longer be enough.

And then there will be commercial demands. Paul Gorman’s analysis in Creative Review is a bit sniffy in places, but his insight on the tension between the audience need for politics, and the business need for ‘seasonal fashion cycles’ reads true.

Church and state will also be a challenge – the Monocle audience may not give a damn about how much branded content is mixed up in their stream, but I suspect The Face may be held to a different standard.

Headlines, editing and curation really matter, but how it looks, reads and sounds mean nothing against how it feels. Tone will be everything.